Category Archives: Uncategorized

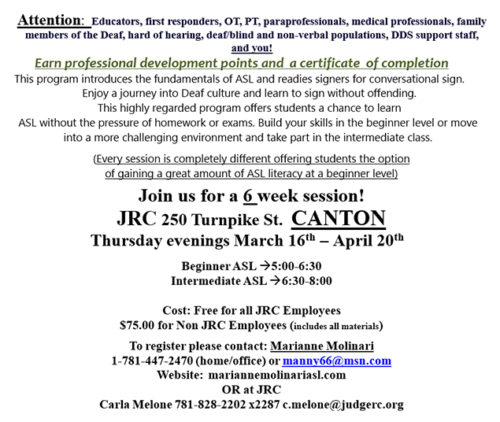

Join us for a 6 week American Sign Language course. Session starting March 16th!

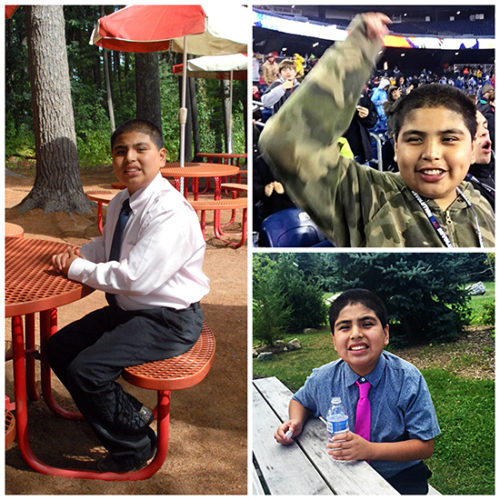

We are very happy to announce Pablo as our Academic Student of the Week.

Pablo has been working very hard in his classroom. He has earned enough academic money to purchase a watch at the Contract Store. He has focused on a variety of tasks including computer work, reading short stories, working on counting tasks, sorting tasks, and a variety of vocational skills. Pablo has been assisting with classroom duties by passing out items to his peers throughout the day, cleaning out the refrigerator, and announcing the classroom schedule change every hour. Overall, Pablo has been doing great! Way to go!

Pablo has been working very hard in his classroom. He has earned enough academic money to purchase a watch at the Contract Store. He has focused on a variety of tasks including computer work, reading short stories, working on counting tasks, sorting tasks, and a variety of vocational skills. Pablo has been assisting with classroom duties by passing out items to his peers throughout the day, cleaning out the refrigerator, and announcing the classroom schedule change every hour. Overall, Pablo has been doing great! Way to go!

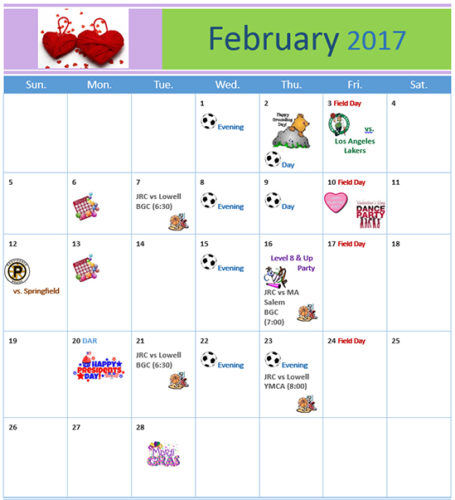

Lots of fun activities coming up this month!

We are very happy to announce that Zavon is our Academic Student of the Week!

Zavon has been doing an excellent job with his schoolwork and completing all assignments on a daily basis. He is a wonderful helper when other students need help on their work too. He recently took a well-earned trip to Dave & Busters. Way to go, Zavon!

Yani celebrated his birthday with Mom at Chuck E Cheese’s!

Selena had a nice visit with her family at Christmas.

Happy Birthday to all our students celebrating this month!

Starting the new year off with some fun activities- basketball, hockey, soccer, and tubing!

Staff and students shopped for and collected new toys for the Toys for Tots program.

Toys for Tots is run by the United States Marine Corp Reserves which distributes toys each Christmas to needy children.